By Ryan T. Conway

The Workshop and me

The ideas and theories of Elinor Ostrom, one of the world's leading economic scholars studying the way people in communities cooperate (or don't), have inspired their own collective action hub. It includes students and scholars of many disciplines as well as people actively involved in managing community water use, organizing fishing industries, delivering urban services, and operating cooperatives. This "hub" is known as the Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis, and is located at Indiana University in Bloomington.

As a graduate student, I sought-out the Workshop in 2010, drawn by the practicality and real-world impact of its "toolkit" as well as the diverse group of scholars and practitioners who make use of it. And this is no small team. Over the years the Workshop has hosted almost 260 visiting scholars, with 18 more on the way for this academic year. This is in addition to its staff, directors, advisory and executive committees, affiliated faculty, and graduate students - all located at Indiana University. This has created a truly global association of what some affectionately call "Workshoppers," or what others call the "IAD network."[1] Through this association, we all share some part of our intellectual heritage, a legacy passed-on from Elinor Ostrom - who asks us to call her Lin.

Lin Ostrom and two "Workshoppers" in 1977. Source: Nobelprize.org

Such international and interdisciplinary diversity - which has endured and grown since the Workshop's creation in 1973 - is a true inspiration and a rarity in the academic world. The fact that people from such a range of different backgrounds can get together and speak with each other - in similar terms and with similar meanings - is a sign to me that something widely applicable and fundamentally accurate inheres in the analytical toolkit that the Ostroms[2] and their fellows have developed. What's even more impressive is the open-mindedness with which the Workshop and Lin evaluate their brainchild. It is quite common to hear Lin, either in class or colloquia, remind her audience that she is always open to suggestions about how her toolkit can be clarified, improved, or interpreted.

In this article, I'll be sketching out the basics of the Workshop and offering my own perspective on how Workshop tools can be translated in a way that both practitioners and researchers can find useful. My perspective is simple and it demonstrates the Workshop's openness while inviting you to join the conversation: shared ideas and common understandings are essential for creating institutions and for analyzing them. Since we speak to share ideas and understandings, we must also reconcile vocabularies to really share interpretations of the world. So here I'll introduce the words and ways of thinking at the Workshop, all in the hope that some common language can help us - collective action researchers and practitioners - work together.

Questioning Conventional Wisdom: Lin's Unique Insight

At the Workshop, we're often warned that "there are no panaceas," which is to say that there's no "one size fits all" solution for problematic situations and no one, final model for the social world, since behaviors and circumstances are constantly changing. Our job, as researchers, is to continually update our models of the social world so that we can explain it more accurately and, hopefully, offer helpful insights to anyone faced with tough choices in a complex, social world. This is important, not just as a practice, but as a way of thinking. Specifically, a way of thinking about how everyday people bring some order to their ever-changing activities. For example: to devise and apply strategies of how "best" to use the resources around us is to practice "economy" with the least ideological baggage in-tow. Every kind of "economy"[3] - whether it's an international capitalist market, a centrally planned national system of production and exchange, or a neighborhood bartering community - comes with its own understanding of the world and notion of what's "best." Hence, when a group of people settles on some common assumptions about the world, like how an economy should operate, things become more orderly. Even better, once they have such a common model of the world, they then can try to clarify specific items, attributes, and relationships that exist, adding even more layers of order.

Contributors from the Ostrom Workshop collaborated in creating supplementary information to assist readers with some of the technical language, basic tools, and key concepts they work with. They include the following three sections:

But what's a model of the world without the people in it?[4] Adding ourselves into the equation requires an act of self-reflection in which we must acknowledge that our rational, intentional, and meaning-making abilities all conspire to help us - and our future generations - to survive. Here, though, is where problems can arise: when everyone in a situation seeks to use available resources individually, the benefits don't always add-up for the group as a whole and can, instead, hurt everyone. This happens when people can't agree on a story about what's going on, or on ideas of what should be done about it. When we have a problem coordinating our ideas, we often have a problem cooperating. We call this kind of situation a social dilemma.

One of the nastier social dilemmas is the "tragedy of the commons." The "commons" could be any type of resource that has uncertain property rights, but much of Lin's work has revolved around resources such as land, water, etc. that communities use to sustain their livelihood. These kinds of resources - like fisheries or irrigation systems - are often "common pool resources" (CPRs), which means that they are limited resources that are hard to manage with property rights. The "tragedy" occurs when a community shares such a resource but has not come to a common understanding about self-restraint or collective management; sadly, then, the resource can be over-used and possibly destroyed. The classic example is an open field shared by all the folk in some pastoralist town. Their flocks are their survival, so, individually, it makes sense to graze them as much as possible. "It's unfortunate that this damages the field," each shepherd might suppose, "but this would happen anyway. If I don't overgraze, someone else will, making me a sucker and threatening my livelihood."

For a long time, many researchers and policymakers believed that the only way to avoid tragedy was to privatize the commons or place them under government control. But Lin wasn't convinced: she saw something else was going on. In fact, she had a fairly radical idea that broke with conventional wisdom: the survival of communities' resources does not depend upon the state to make laws and impose punishments, nor does it depend on assigning a dollar value to every fish, chunk of grass, or drop of water. Rather, people, when they come together, can share understandings and manage their resources by enforcing norms and rules of their own design! The unconventional idea in many quarters was that people could cooperate "beyond markets and states."[5]

Ostrom Receives the Nobel Prize.

Source: The Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis Facebook page.

The Workshop toolkit

Through many years and countless studies of "commons" successes and tragedies, Lin and the Workshoppers developed a toolkit for analyzing these situations. Its use has led to discoveries that have aided practitioners and inspired academics.[6] Each tool can be used to help map-out the different ways a community organizes its actions through instances of decision making, e.g. agreeing on a type of economy and how to run it. In this section, I'll take you through some of the major analytical tools developed at the Workshop. First I'll outline all three tools and their basic uses. If this outline seems a bit overwhelming, don't worry, we'll break it down piece by piece.

The grammar of institutions is something of a master-tool: it allows the analyst to break any social norm or rule down into smaller, more easily understood components, or what I would call the building blocks of social relationships. And, though this is adequate for analyzing any single social proscription, most people make decisions in situations where they face multiple and sometimes conflicting social norms and rules. To help analyze such complex situations, another tool has been developed: Workshopper's call it the IAD or Institutional Analysis and Development framework. If the grammar of institutions is best suited for analyzing any, single social norm or rule, then the IAD is best suited for analyzing any collection of them that occur simultaneously around a single decision. As such, the basic relational building blocks of multiple social proscriptions can be analyzed, simultaneously, using the IAD. Lastly, just as the IAD is adequate for analyzing a collection of social proscriptions that relate to the management of a single, community resource, the social-ecological systems framework (SES) allows the researcher to catalogue all of the critical variables related to the management of an entire social-ecological system. Though this framework is somewhat more general than the other two tools, it can still integrate both of them. Just as one can use the IAD to analyze how choices are made about governing a single community resource, the SES can allow the researcher to classify and make comparisons about how multiple resources - within a larger ecosystem - are managed.

The Grammar of Institutions:

One strength of the Workshop toolkit is that all of its tools are compatible. This has been possible because they have all evolved from one, master tool: the grammar of institutions.[7] This the tool that identifies the basic building blocks of social relationships, and the Workshop has special terms for them. As a simplified illustration, consider a housing cooperative where housemates share and rotate roles, one of which is "waste-manager." In this role, one of the duties is compost consolidation: on the 2nd Friday of every month, the member must empty all the compost containers into the main bin, without opening the container lids inside and without spilling any of the compost. And there is a rule: if the member fails to complete this duty in the manner specified, that member will have to retain this duty for two additional months. Using the five, relational building blocks - which fit the acronym ADICO - one could analyze the waste-manager example in the following way:

- Attributes (to whom does this norm/rule apply): the house waste-manager

- Deontics (may, must not, or must be done): must execute the compost consolidation duty, must not open container lids inside and must not spill any compost)

- Aims (designated actions): empties all compost containers into the main bin

- Conditions (when, where, and how doesit apply): on the 2nd Friday of every month, in the main house

- "Or Else" (agreed upon, specific punishments to be applied when a person acts in violation of the agreed-upon definitions of the other four parts): or else she will remain the waste-manager for the next two months.

Through this example, one can see how we combine these basic relational building blocks to produce a norm or rule that guide people's behavior in a collective action situation. The Workshop refers to these combinations of basic building blocks as institutional statements, which can take the form of rules, norms, or shared strategies. When a group organizes its behavior through a statement that includes all five of these parts, this is a rule. If the group has not specified a punishment - no "Or Else" - this is a norm. When members of the group only have common knowledge about "attributes," "aims" and "conditions" - who, what, when, where and how one must act - the Workshop approach[8] assumes that each person will see the same situation and each, on their own, will come-up with the same solution: this is a shared strategy.

Now, keep in mind that real-life situations occur where people have to take into account several of these institutional statements. To understand how this might work, I'll try to explain how the grammar of institution fits-in with the other tools. The easiest way to picture the relationship between the grammar of institutions and the other Workshop tools - the Institutional Analysis and Development framework (IAD)[9] or Socio-Ecological Systems framework (SES)[10] - is to think about the study of DNA. Just as nucleobases and amino acids can combine in various ways to create many different types of proteins, there are basic building blocks of social relationships that can combine in various ways to create many different types of group behaviors. Life scientists needed specific tools to identify genetic building blocks and still other tools for mapping the biological structures these genetic building blocks create. Social scientists are no different: we needed specific tools to identify the building blocks of social relationships and still others to map-out the larger social structures they create.

The Institutional Analysis and Development Framework (IAD):

To show you how the grammar of institution relates to the other Workshop tools, I'll take you through the basics of the IAD. (As I do this I suggest you link back and forth between the text here and the IAD InfoBox.) Let's return to the example of the waste-manager role in the housing coop. If you think about it, the compost consolidation duty might include three levels of decision-making: (1) a full, house meeting decides to add the role of waste manager to the list of house roles and appoints a subcommittee to determine the specifics of the waste manager role; (2) the subcommittee decides the duties of that role and how they are to be carried-out; (3) the member acting in the waste manager role has to choose whether and how to execute it. Level 1 is a "constitutional-choice situation:" members choose how some rules are to be made. Level 2 is a "collective-choice situation:" members in the subcommittee make the rules, given the "how" guidelines of Level 1. Level 3 is a "operational-choice situation:" the member decides how to execute their waste-manager duties, given the guidelines of Level 2.[11]

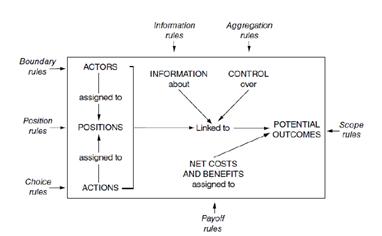

The choice made at each of these three levels represents what Workshoppers call an action situation. To explain this, I'll refer to the figure, below. Within the box, notice the seven major elements: Actors, Positions, Actions, Information, Control, Net Costs and Benefits, and Potential Outcomes. Around the outside of the box, notice that a certain rule points toward each of the seven major elements. For example, look at the bottom left corner: a "choice rule" determines what kind of Actions a person can take.

Figure 1: Action Situation.[12]

Now, recalling that the grammar of institutions is able to analyze each of these rules, one can see that the grammar of institutions and the IAD can be used together, depending on how specific one wants to be in her analysis. And the relationship between the IAD and the SES is quite similar.

The social-ecological systems framework[13] (SES) is a framework that presents a comprehensive list of important objects, relationships, and variables that are necessary for understanding how social arrangements - like norms and rules - overlap with the natural relationships in an ecosystem. (Again I suggest that you link back and forth between the text here and the IAD InfoBox.) Ecosystems are rarely simple, so it's easy to imagine that one ecosystem is composed of more than one community resource.[14] For example a forest ecosystem may have timber, edible products, and a water-source that is channeled into an irrigation system, downstream. Just as our last example showed how the IAD can be used for analyzing the management of one community resource - organic compost - the SES would allows a researcher to identify several resources within a larger ecosystem and, further, allow the researcher to compare how the different resources are managed, using the IAD to look at each resource, respectively.

If each use of the IAD contains three levels of analysis and each level of analysis contains seven rules, you can see how this can all become very complicated, very quickly. However, the advantage of the Workshop toolkit is that, when used carefully, it can bring some consistency and order to how one thinks about these incredibly complex situations. What's more, the tools can be used independently: using the SES does not require using the IAD which, in turn, does not require using the grammar of institutions. One chooses which tools to use, depending on how specific they need to be. If getting through all this "jargon" may not yet seem worth your while, it's worth considering that this is a powerful approach to understanding how people work together, and it has been used by collective action practitioners and scholars around the globe. And, in this case, the payoff is clear: if we can all work from a common understanding - in this case, of Workshop vocabulary analytical tools - we enhance our ability to work together. If you're still not convinced, this next section might change your mind.

A missing variable: how ideas and our words matter

Complex problems in collective action are common to everyday living situations. "But," you might ask, "do we really need all this new vocabulary to describe common experience?" I would say yes, for a very simple reason: our thinking and talking structures and in part determines how we behave, whether we are practicing collective action or researching it. So learning to share ideas and refer to them with the same words will keep us on the same page. And, more than this, I am convinced that both the research and practice of collective action are grounded in what Tomasello[15] calls ?shared intentionality,? or what some political scientists call collective ideation. In other words, effective collective action may, in practice, rely on shared vision ? both of our world and of the goals we seek within it. In a neighborhood bartering system, this may be an idea of what constitutes the neighborhood, who qualifies as a neighbor, what goods can be exchanged, and a stated or tacit goal for beginning the system in the first place. In the Workshop, this is a collective acceptance of the toolkit, itself, as a baseline of shared concepts and models that help us to explain social behavior. Without the shared ideas, it?d be hard to organize a barter system; without the shared ideas, we wouldn?t be a Workshop.

This claim, however, is controversial for some complex reasons. I?ll save apologetics for the endnotes and remind the reader that these thoughts are just my own.[16] But herein lays the beauty of the Workshop: the boundaries of our tools are continually contested, expanded and revised in ways as diverse as the network of Workshoppers, itself. So, let?s jump into the fray.

Whether looking at mainstream or alternative economies, one will always run into some kind of social dilemma, like the tragedy of the commons, mentioned above. Many academics say that beating social dilemmas is a matter of solving the collective action problem. This is a generic way of saying that, in order to achieve a benefit that helps the members of a group, some portion of these people must accept a risk of paying extra for a benefit shared by all. Here is where the Workshop applies its ideas. Such groups can, sometimes, solve the collective action problem using the rules, norms and shared-strategies, noted above. However, none of those institutional statements, nor their relational building blocks, just spring from thin air. In fact, I think that a shared intentionality must be developed ? that is, a collective ideation problem must be overcome - before groups can effectively work together.[17]

The collective ideation problem is a problem of finding and agreeing on common definitions, knowledge, and understandings of a situation, all of which are necessary for creating institutions. Indeed, it's hard to make sense of the "institutional grammar" without them. Crawford and Ostrom note:

By focusing on mutually understood actor expectations, preferences, and "behavior" one avoids the trap of treating institutions as things that exist apart from the shared understandings and resulting behavior of participants.[18]

Other economic scholars would agree. Denzau and North wrote a widely received article explaining the importance of sharing understandings, or what they call "mental models."[19] And, further, Diana Richards, Whitman Richards, and Brendan McKay have contributed to our understanding of how mental models affect choice, modeling how shared knowledge structures affect how people behave in social dilemmas.[20]

Mental models are how we organize and make sense of the world. Mental models are useful, simplified versions of the social and ecological worlds we live in, just like a map is a useful, simplified version of a territory, or a blueprint is a useful, simplified version of a building. When we try to expand these models - to understand our place in the world, the relationships among all the things in it, and what we should be doing - we typically do so by remembering ideas we've learned from experience, books, or other media. But we also tend to test and develop our ideas by talking them through with others.

A Group photo of Workshoppers.

Source: The Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis Facebook page.

I'll use a very simplified situation to illustrate the importance of collective ideation. For example, if you and I live in a fishing village - far away from the nearest major trading port - we might try to imagine the most important aspects of our livelihood: (a) we're dependent upon the bay to harvest most of our food; (b) the bay has stocks of crab and tilapia, which each of our families, respectively, fish; (c) the geographical boundaries of the bay are not visible; I have never been to the edge of the bay and believe it to be limitless, whereas you have seen the edge and realize that it is limited; (d) being so far away from a major trading port, it is easier for me to trade three of my tilapia for one of your crabs than to sell the tilapia in exchange for currency; (e) it is possible for me to harvest more tilapia than you are willing to trade for or that I am willing to eat, (f) I believe it's impossible for us to fish so much that the crabs and the tilapia die off; however, you grew-up in a fishing village that overfished and destroyed its stocks.

Now, if we don't talk through our differing mental models of the fishery, there is a collective ideation problem, because we hold conflicting understandings of our resource. For my part, I will be more likely to overharvest because I am unaware of the physical boundaries of the bay, I am unaware of the very possibility of overfishing, and I have little idea about how much tilapia you are generally willing to trade. However, if we can talk through our different ideas of how our shared world is structured and how it works, we could arrive at a "shared framework of mental models that groups of individuals possess that provide both an interpretation of the environment and a prescription as to how [it] should be structured." (ibid) If we achieve this, the soil is ripe for developing shared strategies, norms, and institutions to help us manage our resource sustainably. This is how people intuitively seek to solve the collective ideation problem, which I claim is necessary, in practice, for us to work together and solve our collective action problems. I think there are many examples in Ostrom's work that support this; however, that's an insider chat for another day.[21]

So how can we move forward from acknowledging that shared ideas and language are important for developing effective institutions? Some research has shown that work within an organization improves through breaking jargon barriers and sharing mental models.[22] Further, we all know how difficult it is to start-up, expand, or replicate grassroots collective action projects, such as community supported agriculture programs, neighborhood barter systems, producer and consumer cooperatives, etc. Success in such ventures may very well depend on how much effort is put into resolving the collective ideation problem before working out a scalable solution to the collective action problem. By this, I mean that it may make sense to focus on advocacy, public education, and demonstrating the benefits and feasibility of solidarity economies. These would be important steps toward developing common understandings with wider audiences. Forging common ground with groups that have different mental models and vocabularies would make it easier for all involved to act collectively. If we mean to show people the merit of a new way of living and working together, we must often use their words and acknowledge their assumptions so that we might, first, change their thinking.

I hope that my explanation of some of the vocabulary and tools that Workshoppers use, as well as my perspective, as a slightly-unorthodox institutional analyst, has been helpful. I encourage you to explore the Workshop toolkit and contact Workshop researchers to brainstorm ways of working together. Though some of our tools may seem overly abstract, formal, and mathematical, I stress that they have little use without your input on the real, live details that you experience as leaders of intentional communities, members of various coops, and folks, just like us Workshoppers, who deal with collective action every day. If any of this seems obscure, check out Mike McGinnis's article on Workshop language[23]; and if any of this raises questions, email me[24]. Let's get to know each other's words and forge some common understandings. I'm sure this will be a good conversation.

The permanent link to this article is http://geo.coop/node/650.

Go to the GEO front page

About the author

Ryan T. Conway is a member of the Managing the Health Commons research team at the Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis and is entering his third year in the Political Science PhD program at Indiana University, Bloomington. Exploring the subfields of Public Policy and political science research Methods, he has studied forestry policy, humanitarian aid coordination, and community healthcare systems. Behind all this is his interest in how negotiating a common perspective - or "framing" - of a problem can promote cooperation in otherwise competitive environments. His personal research interests include emergency management, sustainable urban design, community economies as commons, and the relationship between public health and the built environment.

His email address is rtconway@indiana.edu

Citations

When citing this article, please use the following format:

Ryan T. Conway (2011). Ideas for Change: making meaning out of economic, institutional diversity. Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO) Newsletter, Volume 2, Issue 9. http://geo.coop/node/650.

Endnotes

[1] The IAD is one of the analytical tools developed at the Workshop. See the related InfoBox.

[2] Vincent and Lin Ostrom advocated for the creation of the Workshop since 1972, with the idea that political theory could be developed as an analytical tool for guiding policy analysis and empirical studies.

[3] It should be noted that there is no "the economy." All societies have many diverse economies that operate at different scales within any given society, like gift economies, barter economies, alternative currencies, etc.

[4] Note: issues of power-disparities, race, class, gender have not been formally integrated into the frameworks, but some Workshoppers have pursued such issues, for instance:

Clemente, Floriane. 2010. "Analysing Decentralised Natural Resource Governance: Proposition for a "Politicised" Institutional Analysis and Development Framework." Policy Sciences 43(2) (June): 129-156.

[5] Ostrom, Elinor. 2010. "Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems. American Economic Review 100(3) (June): 641-672.

[6] Cox, Michael, Gwen Arnold, and Sergio Villamayor Tomás. 2009. "A Review and Reassessment of Design Principles for Community-Based Natural Resource Management." Submitted to Ecology & Society.

[7] Crawford, S. and E. Ostrom (1995). "A Grammar of Institutions." American Political Science Review 89(3): 582-600.

[8] This assumption isn't unique to Workshop thinking, but stems from a large body of research in "game theory," an approach to analysis that assumes people make decisions by calculating the costs and benefits of each option in a choice. This approach has created many powerful, mathematical models, but it assumes that the way each person makes choices is, essentially, the same and, of course, this is a hotly contested assumption.

[9] Ostrom, Elinor. 2005. Understanding Institutional Diversity. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

[10] _____. 2009. "A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems." Science 325(5939) (24 July): 419-422.

[11] See link to "Levels of Analysis and Outcomes."

[12] _____. 2005. Understanding Institutional Diversity. Princeton: Princeton University Press: 189.

[13] ____. 2007. "A Diagnostic Approach for Going Beyond Panaceas." PNAS 104(39) (September

25): 15181-15187.

[14] See link to diagram of the SES and its major components.

[15] Michael Tomasello, Malinda Carpenter, Josep Call, Tanya Behne, and Henrike Moll 2005. "Understanding and sharing intentions: The origins of cultural cognition." Behavioral and Brain Sciences 28, 675-735.

[16] Few have directly addressed the tension between game-theoretic and ideational approaches. Though it was left relatively undeveloped, Diana Richards broke interesting ground when crafting some elegant formal models that sought to integrate and understand the effects of shared, empirical mental models on performance in coordination dilemmas. See:

Richards, Diane. 2001. "Coordination and Shared Mental Models." American Journal of Political Science 45(2): 259-276.

[17] Legro, Jeffrey W. 2000. "The Transformation of Policy Ideas." American Journal of Political Science 44(3): 419-432.

[18] Crawford and Ostrom 1995: 583

[19] Denzau, Arthur and Douglass North. 1994. "Shared Mental Models: Ideologies and Institutions" Kyklos

47(1): 3-31.

[20] Richards, Diane. 2001. "Coordination and Shared Mental Models." American Journal of Political Science. 45(2): 259-276.

Richards, Whitman, Brendan D. McKay, and Diana Richards. 2002. "The Probability of Collective Choice with Shared Knowledge Structures." Journal of Mathematical Psychology. 46: 338-351.

[21] For example, regarding one of the most basic of the institutional statements - shared strategies - Lin notes that:

All players must share common knowledge that all have adopted a strategy in order for it to be an institutional statement. If all players do not consider it prudent, the strategy is not shared and will not work (Crawford and Ostrom 1995: 592).

Just as well, I think that the unofficial costs for breaking social norms - guilt, ostracism - and the official punishments for breaking rules - fines, prison time - depend on shared understandings that are even deeper than common knowledge in a single situation. Further, as situations change, people must adapt. Ostrom notes that mental models affect learning and describes how people update their models when experience shows their model to be flawed (Ostrom, 2005). Mental models of how a local environment and people interact are also critical for understanding resource users in one Ostrom's SES framework (Ostrom 2007, 2009). And, lastly, in a primer article on the language and concepts of the Workshop McGinnis claims that , "cultural dispositions" are integral to the deepest level of institutional analysis, while "cultural repertoires" are a critical component of communities that are studied (McGinnis, 2011: 173, 176).

Mental models, worldviews, and the cultural histories that affect them, can each be interpreted as a source of common understanding. Though interpretation is a qualitative process that most quantitative scientists shy away from, Ostrom confronts it directly, noting: "The incompleteness of most existing rule systems becomes even more apparent when we recognize that the attributes and conditions of situations may be interpreted in different ways" (Crawford and Ostrom 1995: 596). She further notes that some interpretations are important enough to be matters of strategic political contests: "Much of political persuasion involves efforts by actors to convince others that the new circumstances match the conditions of a rule - that is in their best interest? (ibid).

[22] Cheng, Joseph. 1984. "Paradigm Development and Communication in Scientific Settings: A Contingency Analysis." The Academy of Management Journal 27(4): 870-877.

Senge, Peter. 1990. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York: Currency/Doubleday.

Boland, Richard J. Jr. and Ramkrishnan V. Tenkasi. 1995. "Perspective Making and Perspective Taking in Communities of Knowing." Organization Science 6(4): 350-372.

[23] McGinnis, Michael Dean. 2011. "An Introduction to IAD and the Language of the Ostrom Workshop: A Simple Guide to a Complex Framework." The Policy Studies Journal 39(1): 169-183.

[24] rtconway@indiana.edu

Add new comment