cross-posted with permission from Medium

“Is there hierarchy in sociocracy?” is a fairly common question. And since people expect me to say no, I always say yes. Why? Because that’s the best way to get into a real conversation. Because the real answer needs to be given in a conversation, not in a quick statement, and not in a slogan.

The question about hierarchy is a question similar to “Are there bosses in sociocracy?” As you might be able to guess, I’d say that there are bosses in sociocracy. I hope you are at least a little bit surprised! Haven’t we heard so many headlines about flat organizations, boss-less organizations and self-organizing? How can sociocracy, which served as the basis for holacracy, involve hierarchy? Wasn’t the promise that all would be different, more shiny and even more effective without bosses?

The question about hierarchy is a question similar to “Are there bosses in sociocracy?” As you might be able to guess, I’d say that there are bosses in sociocracy. I hope you are at least a little bit surprised! Haven’t we heard so many headlines about flat organizations, boss-less organizations and self-organizing? How can sociocracy, which served as the basis for holacracy, involve hierarchy? Wasn’t the promise that all would be different, more shiny and even more effective without bosses?

It all depends on how you interpret “hierarchy”, or “boss”. If “hierarchy is a system or organization in which people or groups are ranked one above the other according to […] authority” (wikipedia definition of hierarchy), then the answer is clearly no, there is no authority in sociocracy in the sense that someone has power over you. But there certainly is hierarchy.

Hierarchy = Tiers of Specificity

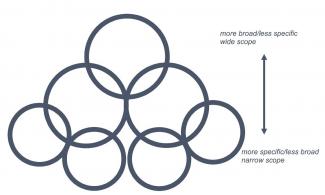

However, there is hierarchy, but it is not hierarchy of people. It is a hierarchy of levels of specificity. The questions a work group (circle) will deal with on a shop floor will be different from the questions asked in a circle that does 5-year planning. This does not mean that one tier is more valuable or more difficult. It only means that they are different levels to pay attention to. Everyone, in their personal lives, makes decisions in a narrow scope (What am I eating for lunch?) and decisions that have a larger impact (Am I moving abroad?). If we walk around addressing only the question of whether or not we are moving abroad, no one is cooking lunch. If we only focus about meal planning, then we will ignore other areas of our lives. But then again, if I think about moving plans while I am cooking, my meal might not be the best I ever cooked. What I am pointing to are three insights:

- Every organization comes with different levels of specificity.

- All of those levels need to be taken care of.

- We will get better results if we focus on the level that we’re dealing with in the moment.

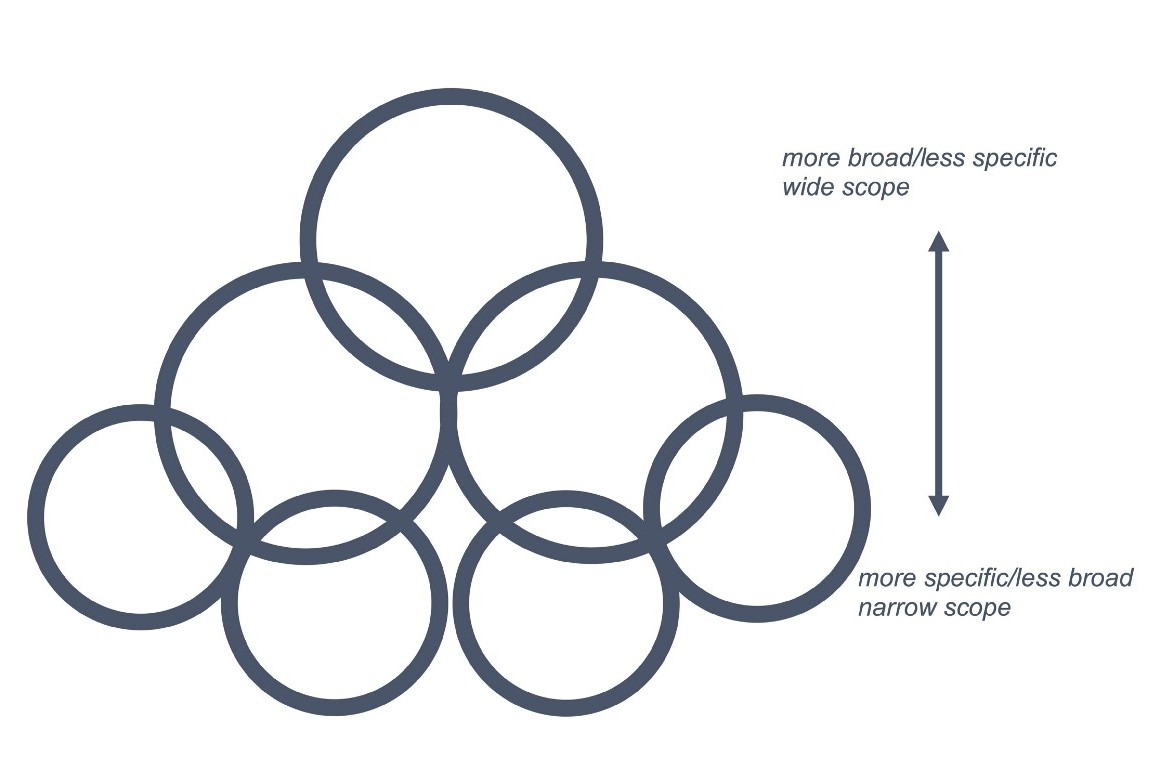

In this way, there is hierarchy of circles. In an organization managing a shared exercise room, some people might focus on the weights. Some might focus on the treadmill. Some might oversee the cleaning. All of those jobs need doing. Another way to look at it is: let’s organize all the toys in your kid’s room. Toy cars go into boxes. Boxes go into bins. Bins go onto shelves. A place for everything and everything in its place. There is no moralistic judgement. Toy cars are not worth less than bins or shelves. What nested domains of authority give us is simply clarity about who takes care of what. In trainings, we often do this little sleight-of-hand of turning an organizational structure by 90 degrees once participants got used to seeing it one way. Each of the organizational structures below is an accurate description of nested circles. And each comes with the same hierarchy of broad to specific, or specific to broad.

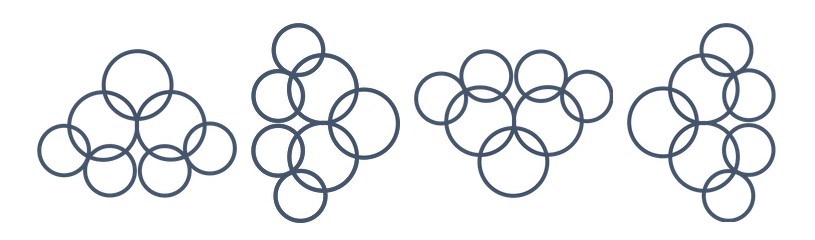

Now that we have talked about what kind of hierarchy there is, let’s talk about what kind of hierarchy there is not. It is not a hierarchy that involves power-over or dominance. In sociocracy, nested circles are double linked: two members of one circle are at the same time full members of the another higher/lower, broader/more specific circle.

Decisions are made by consent, i.e. a decision can only be made when no one has an objection. That means that practically, a “higher” circle can only make a decision with the consent of its members who are also members of its linked “lower” circle.

Decisions are made by consent, i.e. a decision can only be made when no one has an objection. That means that practically, a “higher” circle can only make a decision with the consent of its members who are also members of its linked “lower” circle.

Double linking in combination with consent decision-making not only prevents power-over but it also serves flow of information. The “higher” circle will hear about what the “lower” circle is up to, and vice versa. Traditionally, the leader of the “lower” circle represents the top-down link, while the delegate (or rep) forms the bottom-up link. Information can flow in both directions, always balancing out power and gaining transparency. The more we know about what other circles are planning and what their struggles are, the better we can consider their needs. This reduces friction and increases effectiveness within and between teams.

Are leaders bosses?

Every circle has a circle leader. Does a leader equate to a “boss”? Just like hierarchy does not imply power-over, being a leader does not imply being a boss. Having a leader of a circle makes sense because it is easiest for one brain to be be paying attention to the whole. The leader does not have to do all the work, neither does she have to do none of the work. All circle members contribute but the leader is making sure everything gets done. All circle members are 100% responsible but the leader has a specific task to pay attention to the whole — a chief among equals.

There are bosses!

What is important to keep in mind is that the leader — just like all other circle members — is constrained by policy decisions that guide what is done and how it is done. Policy is made by the circle, by consent. Since everyone is bound by policy made by the circle, saying that there are no bosses in sociocracy is not accurate if “no bosses” means that everyone can do what they want all the time. Sociocracy is certainly not leader-less. The leader holds people accountable to what they consented to do. (And listens to what obstacles are in the way.) If you really want to use the term “boss”, then the circle is the boss, and the leader is the assistant or executor of the boss. Since you are part of the circle, you’re your own boss, together with your circle mates.

There are no bosses!

Leaders in sociocracy are more like running partners. You decide together how far you’ll run and how fast. In an organizations, that would be the policy level. You could run alone, the same distance at the same pace. But it is easier to get out of bed and be accountable when your running partner is waiting for you, holding you accountable your promise of being there at 6.25am! Does it involve power-over? Not at all. You’re there because you choose to. So it is not accurate to say that there are bosses if “boss” means power-over. All the slogans around bosses or no bosses are a simplification that does not do justice to the way power and accountability are balanced and shared in circle-based governance.

Hierarchy of Specificity and Roles

As circle members, individuals will fill roles within the domain of their circle. A simple example: imagine a circle that takes care of all the shared space of an organization (kitchen, exercise room). The kitchen circle might have a “fridge czar” — the role that oversees the fridge. This person makes sure that no mold spreads between the sandwiches and reminds people to put their name on their lunches. When there is policy to make (for instance, “do we form a small budget for shared common goods like milk for coffee?” or “can unlabeled food be eaten by anyone?”), the circle will make these decisions by consent. The fridge czar makes sure things happen smoothly and within policy. Roles do not need permission for everything; within existing policy, they have authority to act. The domains of roles will be subsets of the domain of the circle they belong to. (Sidenote: in sociocracy, not every subset of the domain of the circle needs to be within a role, i.e. the circle can hold responsibilities as a circle that are not held within an individual role.)

Just like in holacracy, a person can hold more than one role. The office fridge czar can be holding the social media guru role at the same time, and might be taking care of the servers. That means that roles are in relationship to each other and to circles whose domain those roles are in — not people. This is the distinction that is inherent in sociocracy and was called “roles, not souls” in the holacratic discourse. Roles are hierarchic in the sense that they belong in the domain of a circle and the circles themselves are organized in tiers of specificity. The point people try to make is that neither holacracy nor sociocracy pigeon-hole people, just roles. That sounds like semantics but it is not. Especially when you consider that one person will fill several roles throughout the organization, depending on their skills and interests. The implications of this are:

Just like in holacracy, a person can hold more than one role. The office fridge czar can be holding the social media guru role at the same time, and might be taking care of the servers. That means that roles are in relationship to each other and to circles whose domain those roles are in — not people. This is the distinction that is inherent in sociocracy and was called “roles, not souls” in the holacratic discourse. Roles are hierarchic in the sense that they belong in the domain of a circle and the circles themselves are organized in tiers of specificity. The point people try to make is that neither holacracy nor sociocracy pigeon-hole people, just roles. That sounds like semantics but it is not. Especially when you consider that one person will fill several roles throughout the organization, depending on their skills and interests. The implications of this are:

- Every individual might fill some roles that are more specific and some that are more abstract. I myself am a good example. In a sociocratically run cohousing community of about 90 people that I am a part of, I currently hold the role of the one re-stocking the kids room with art supplies. I wash the windows of the community building. I also am facilitator of one of the department circles. And I am the one who convenes the General Circle. Every member can mix their own blend of roles that suits them.

- What makes this approach so appealing is that roles are fine-grained enough to allow flexibility over time. When, for instance, a member has a young child, it is easy to temporarily phase out of some of the roles and pick up other roles in a dynamic manner.

- Overall, in a sociocratic world, we can also combine our roles according the level of attention we want to pay. For instance, though I might not be paying attention to the overall planning of my girl’s middle school sport team, I might be willing to bake a cake for them from time to time. Also, I confess, I do not pay attention to the school Parent-Teacher-Association. But I am part of the local time bank and oversee the onboarding of new members. Our time and, more importantly, our attention is limited. An approach like sociocracy that allows for roles allows for a dynamic life balance. Sometimes we are worker bees — “just tell me what to do” — sometimes we are part of the decision-making on different levels of specificity.

To be Heard. Healing and Retraining.

We all grew up immersed in autocratic and oppressive systems. Power-over is all around us. For some of us, it is hard to imagine hierarchy without power-over — in our experience, they always go together. Since it is such a strong influence on us, just “getting rid of power structures” is not enough to truly leave them behind. It takes more than just a lack of formal power-over to heal. I have encountered many people who assume power-over even where it is not — and I myself sometimes catch myself operating from lack of trust, assuming to be disadvantaged or outnumbered. Also, power can sneak in the back door. Just because we’re equals on paper, that does not mean we’re equals in practice. (This is almost too trite to say out loud.) Disregarding power dynamics, like not acknowledging priviledge, only works in support of those underlying power dynamics. Therefore, I am skeptical when I hear an organization say they are “without hierarchy”. They have to practice equality. Experiences of power-over will trigger reactions on an emotional level, and we have to create a space to talk about those reactionsinstead of declaring power dynamics absent or “dealt with”. The more issues are out in the open, the more room we have to address them.

We all grew up immersed in autocratic and oppressive systems. Power-over is all around us. For some of us, it is hard to imagine hierarchy without power-over — in our experience, they always go together. Since it is such a strong influence on us, just “getting rid of power structures” is not enough to truly leave them behind. It takes more than just a lack of formal power-over to heal. I have encountered many people who assume power-over even where it is not — and I myself sometimes catch myself operating from lack of trust, assuming to be disadvantaged or outnumbered. Also, power can sneak in the back door. Just because we’re equals on paper, that does not mean we’re equals in practice. (This is almost too trite to say out loud.) Disregarding power dynamics, like not acknowledging priviledge, only works in support of those underlying power dynamics. Therefore, I am skeptical when I hear an organization say they are “without hierarchy”. They have to practice equality. Experiences of power-over will trigger reactions on an emotional level, and we have to create a space to talk about those reactionsinstead of declaring power dynamics absent or “dealt with”. The more issues are out in the open, the more room we have to address them.

In that sense, healing from power-over takes time, awareness, practice and an intentional effort. One way sociocracy offers this is by doing rounds. When we get used to speaking one by one, we can counterbalance difference in traditional holders of power (may it be power through rank or through privilege). Declaring everyone equal on paper and not sticking to process in who talks when and for how long reinforces inequality. Being part of a circle — participating together, truly as a group — is transformative because it lets us practice equality in both senses of the word: (1) equality in put into action, for instance by doing rounds or double linking. (2) And practice in the sense of training ourselves. Equality has no “on” switch. We have to listen and speak up again and again to weed out our expections and patterns that we have learned. As we gain trust that our organization will not exercise power-over, we are re-training ourselves so we can heal.

Learn more about Sociocracy/Dynamic Governance here

Go to the GEO front page

Add new comment