Excerpt from Comprehensive Economic Theory

Translator’s note:

This excerpt is a side hustle, so to speak, a departure from my ongoing work on the translation of Cooperative Enterprise and Market Economy. As in all side hustles, I had practical reasons: for past couple of years, I have been working with fellow members of a “learning-action circle” focused on cooperative approaches to local food system organizing.

One stumbling block has been the concept of “the consumer,” a title and role that seems too limiting, as if our only role were to buy the food and eat it, composting the scraps. Our agency would be limited to choosing between supermarkets and the buyers club or farmers market. Likewise, our “needs” as consumers are often reduced to some combination of survival and consumerism. The reality of our practice doesn’t match this, together with local farmers, food sovereignty activists, bakers, educators, and more we have been building the social-economic relationships we need in order to become capable of sustained collective action.

We are not alone; Equal Exchange uses “citizen-consumer,” a term I find problematic since, in the US at least, “citizen” is used to exclude undocumented people, some of them key players in the food system (obviously, that is not how E.E. uses the term). Farm tech developer Jamie Gaehring has suggested “metabolizers.” Mike Hales, who writes on commoning and technology, prefers the language of provisioning, which integrates a range of activity and roles, so maybe we are provisioners?

The lack of a good term is the sign of the lack of an adequate conceptual framework, which is where Luis Razeto comes in. Over the course of his career, Razeto has worked to articulate a theory of economics suited not just to capitalism but to the spectrum of economic relations, especially those based on cooperation and solidarity. His work has been a spiral of practice, reflection and exposition, circling back to previous concepts and questions only to raise them to a new level, integrating them into his developing theory and spinning off new lines of inquiry. Comprehensive Economic Theory is a fine example, drawing on the first two volumes of Economía Solidaria y Mercado Democrático (1984), which were later updated and republished as Las Donaciones y la Economía de Solidaridad (2018) and Crítica de la Economía, Mercado Democrático y Crecimiento (1994); as well as Cooperative Enterprise and Market Economy (2023, GEO.Coop). The ideas here are futher developed in Desarrollo, Transformación y Perfectionamiento de la Economía en el Tiempo (2000); Lecciones de Economía Solidaria (2009) and Tópicos de Economía Comprehensiva (2017).i

This should be considered a working version of the text, not a final product. I welcome suggestions and comments.

-Matt Noyes

Chapter 15.

The Satisfaction of Needs and the Use of Products

65. - In the previous sections we examined the processes of production and circulation, laying out the foundations of their respective general theories. We now turn to the central questions of a general theory of economic consumption.

In Economics, the theme has scarcely been considered from a theoretical standpoint. Consumption is taken into account as a relevant economic variable, but in a very restricted sense – as “consumer spending” – as opposed to savings and accumulation. At the micro-economic level, the focus has been on consumer behavior in an effort to understand consumers’ disposition to spend, in relation to their drive to accumulate revenue and wealth, as well as the way variations in price affect spending. On the macroeconomic level, consumption is an aggregated variable – total consumer spending in the economy – which, when added to investment, equals total income. These questions are secondary in our analysis, absorbed in a larger thematic which we will examine within a very different conceptual framework.

Only some dimensions of the process of consumption have been considered from a theoretical point of view, particularly in the study of “welfare economics.” In these analyses, aspects proper to the theory of consumption are combined with those belonging to the theory of circulation, and all of it is definitively reduced to policy criteria approximating Pareto’s optimal distribution.ii In any case, the themes and matters that we consider here as part of the theory of consumption have not been the object of systematic economic theorization, and our own elaborations should not be seen as more than a first step.

And yet, consumption is of maximum importance for the theory and practice of Economics, being one of the essential constitutive aspects of economic activity, the one in which its objectives are attained. It is a fundamental moment in the economic process without which its circularity can neither be realized or understood.

By disregarding the study of consumption, the science of Economics runs the risk of theorizing the general economic process with no regard to its ends, concentrating only on the dimension of means, turning Economics into a merely instrumental discipline, a “subordinate clause” of positivist scientism. Consumption is the final phase of the economic circuit in which the process as a whole is fulfilled and its meaning revealed. To disregard it would be to make Economics irrelevant as a guide to human activity, abandoning that responsibility to other disciplines and practices, such as political theory or to one ideology or another. It is not the job of Economics to define the ends and ultimate objectives of human social activity, including economic activity, and yet, adequately broadened, Economics can offer important elements needed to construct a new understanding of this truly decisive question. An economic theory of consumption acquires, in this sense, a special importance.

It is not only a question of the objectives and meaning of the economy, but also of key aspects and practical options arising in the processes of production and circulation. A theory of consumption enables us to reframe relevant dimensions of economic growth and development, which are determined not only by the percentages of income destined to be spent on consumption and investment, but to a large extent by the modes and rationalities of consumption and its process and activities.

Now, in distinguishing the consumption process from the processes of production and circulation we are drawing a division in the same way as we did between the two latter terms, that is, understanding that the difference between processes of consumption, production, and circulation is an analytical distinction rooted in reality. We are dealing with aspects and moments of a global economic process which reciprocally condition and require each other. There are many consumption activities in the processes of production and circulation, just as consumption includes activities of production and circulation. But if we take a given product as our unit of analysis we can distinguish a sequence of stages and activities: first it is produced, then circulated and distributed, and finally consumed. In this sense consumption constitutes the terminal moment of the economic process, although it should not be forgotten that consumption is also the beginning of a new cycle.

In each phase – production, circulation, and consumption – we can recognize movements or flows of economic goods, and in the same three processes we see that those goods are transformed; but the economic meaning of these movements and transformations varies with the structures or systems of relationships to which they belong. It is precisely in and through these differences that theory identifies and distinguishes them. What, then, is consumption?

By consumption we mean the utilization of goods and services in the satisfaction of needs, aspirations, and desires of economic subjects. Through consumption, products provide the specific utility for which they were created.

Like any economic process, consumption is made up of combinations of activities and relations. It is itself an economic activity, the elemental form of which is the act of consuming. Considered in general terms consumption is a complex process, so it is better to begin the analysis with its simple form.

In the act of consuming there are two constitutive elements at work: the consuming subject and the economic good consumed. The subjective element is the principal one because it is the subject that carries out the activity through which the economic good provides its utility. The subject is the active element in the act and social relations of consumption; it is consumption’s principal and its end. The subject acts on the economic good, which thus becomes the passive element in the relationship, the means whereby the subject is satisfied. Economic theory needs to take into account both elements as well as the relations that they establish and that which happens to them in the act of consumption.

In theoretical terms, we must first identify the subjects of consumption. This requires precise observation of the practices and relations of those who consume economic goods and services. In general terms, the subjects of consumption can be natural people, communities, social groups of any type, institutions, enterprises, the State, or any other entity that uses economic products to satisfy some human need, aspiration, or desire.

We understand consumption, then, to be an especially human activity and we do not recognize as subjects of consumption a machine burning oil or fuel, a plant assimilating fertilizers or being treated with pesticides, nor a pet being fed from a can. These modes of utilization of products of human labor are indeed acts of consumption, but the subjects are not the machine, the plant, or the pet but the humans who decide that these goods should be utilized in this form, thus satisfying their own needs or desires to employ machines, cultivate plants, or feed pets.

While they are always human, the subjects of consumption are not always individual people or groups of individuals. Human realities sometimes have vague contours, presenting as conglomerates lacking individuality. Some products are utilized in a diffuse manner and provide services through a progressive expansion of their range of action. We are thinking, for example, of cultural works, police services, methods of atmospheric decontamination, etc.

Observation of the subjects who utilize and benefit (or suffer) from goods and services leads us to the concept of “externalities” (positive and negative). With this concept – which is applicable not only to products but also to processes of production and distribution – economists identify those effects that certain goods and activities have, beyond the qualities seen and sought by the subjects who make the corresponding purchase. They are effects that fall on third parties who are not directly involved in the spending or on the community as a whole.

Such a conception of externalities certainly has use in conventional Economics, where it permits one to take into account an immense quantity and variety of economic effects that are not explicitly identified in models of analysis centered on processes of exchange and limited to activities and goods that are assigned monetary value. But this concept, precisely because it performs this function, in fact serves to hide substantial economic realities which then go without the attention that they deserve, because it is believed that sufficient consideration and explanation has been provided just by giving them a name.

If the notion of externalities reveals some awareness of the social effects of economic activities, it does it in a way that is so insufficient and “ashamed” that it ends up serving rather to justify a conception or structure incapable of truly accounting for all the social dimensions of consumption (and of production and circulation).

We said, then, that the subjects of consumption are the people, enterprises, communities and groups of people, and society as a whole. Now, we can better specify the subjective and active elements by considering the acts of consumption as linked in both a temporal sequence and a spatial articulation, as a process of complex consumption.

The “temporal sequence” refers to the series of successive transformations, in each of which the goods or services transfer their utility, in part or in whole, and are consumed. We already underscored this fact when examining the difference between markets of factors and markets of products. We saw that the products of economic activity are usually utilized sequentially in different enterprises, in the form of production inputs and factors. This productive consumption differs from final consumption, and we see that various goods and services are consumed by different economic subjects in a chain that links not just units or cells of production but also successive units or cells of consumption.

In a “spatial” sequence a given good or service is utilized in the same or similar way by a variety of economic subjects, none of which exhausts the utility of the product which remains available for others to use to satisfy their own needs and desires.

Taking into account these temporal and spatial linkages we can identify in concrete terms the various types of subjects that play a role in economic consumption, and the social dimensions of the process. But this same awareness of the linkages leads us to understand that the consumption’s essential form is revealed when finished economic products are utilized, those products involved in the final transformation in which their definitive utility is transferred directly to people. It is final in the sense that it is to this end that all the previous transformations and acts of consumption were effected. So we can say that the ultimate or definitive subjects of consumption are the natural persons who use given economic products to satisfy their needs, aspirations, and desires.

To acquire a clear grasp of the subject of consumption, we need to spend some time on the concept of the reality of human needs, beginning with the objective element in the act of consumption.

In general terms, an object of consumption is any product of economic activity, that is, any good or service, material or immaterial, tangible or intangible, created through some productive process in an economic unit and distributed via the market through some circuit of economic relations.

As broad as it is, this formulation of the object of consumption can give rise to a narrow and reductive understanding if important aspects that we have underlined throughout our investigation are forgotten. In the first place, we have considerably broadened the concepts of “economic unit” and “market” with respect to conventional understandings.

In the second place, we have stressed the subjective character of economic realities, especially with relation to the economic resources, factors, and categories and the forms of domination over economic goods in general. When using the term “object of consumption” we should recognize the subjective character of these objects as products of economic activity. They are the result of activities into which working people and communities have “poured” their subjectivity, their power, their sensitivity, and their feelings. Products combine in some way the resources, factors and categories that go into their production, thus collecting and synthesizing the subjectivity proper to these elements which we have amply documented. We will deepen the analysis of this subjective dimension of products after considering the various types of human needs in the satisfaction of which they are utilized.

When we identify products as the “objective element” and as the “object” of the act of consumption, we are not alluding to the intrinsic nature of the products themselves – remember that we are referring as much to immaterial and intangible goods as to those that are material and tangible, all created by people to satisfy needs that are spiritual, cultural, relational, etc. – but to the fact that in the act of consumption and in the framework of relationships that it implies, products take the passive part in the relation. It is the subject that decides whether and how to consume them.

In the third place, the same broadening that we applied to the subject of consumption also applies to its object, giving rise to an extraordinary widening of the concept. If our definition of the subjective element of consumption incorporates all the subjects who are linked temporally and spatially to the goods and services involved in the process of consumption (including those referred to as “externalities”), then the objective element of consumption should include all the elements and aspects of the products that give rise to and reveal this range of effects and their complexity. The economic good or service is defined not only by that part of the object of consumption that directly satisfies the need or desire of the person who consumes it, but by all of its various dimensions and aspects that have impact on human needs and desires. For example, the consumption of gas in automobiles includes the effects of the pollutant carbon dioxide on citizens. Having been produced together with, and as a part of, the good or service in question, such dimensions and aspects are also consumed, for better or worse.

We will return to the object of consumption after examining the process of its transformation and the human needs in function of which it is produced. On this basis, we can deepen the question of the “goodness” of goods and the “serviceability” of services, which we noted when we talked about the efficiency of markets and when we mentioned the negative effects and “externalities” of some products.

Let us now examine what happens to the subject and object of consumption in the act of consumption. Seen from the point of view of its objective element the act of consumption is the ultimate stage of the process of transformation that a produced good or service undergoes, that in which it ceases to be what it is and leaves the economic circuit definitively, (or else is reintegrated into it in a different form, as part of a new economic factor).

Products experience something like a life cycle in the course of which they pass through different phases. The first is the one in which they are elaborated or created, and can consist of a unique process of production or a sequence of successive transformations. The second phase consists of the movement by which the product arrives in the hands of the person who demanded it, and can also happen in one moment or as a succession of displacements and transfers in which it passes from one subject to another until reaching its final destination. The third phase is that of consumption, in which, through a simple act or a series of small transformations which unfold in time the product ceases to be what it is, disintegrates as such or else is modified and incorporated into a different reality. Consumed, or depleted, ended, it can be said that the product has fulfilled its mission, delivering its utility (its use value) to those who consume it.

It should be observed, nonetheless, that the utilization of products assumes a wide variety of forms and modes depending on the type of goods or services in question, and the needs they satisfy. In some cases the product’s utilization simply consists of a “being there” of the object, which fulfills its function merely through its presence. Think of a decorative object which provides utility when exhibited in a place, or a certain quantity of wealth that satisfies a subject’s need for security and desire for social prestige by the sole fact that the subject “has” it and considers it their property.

In other cases, the product’s utility is transferred through “doing” something. This is true of foods that are eaten, a bicycle that is ridden, a book that is read. In each case it is through the action that the need is met.

Finally, utility can be provided when the good or service “grows and develops,” its utilization consisting in this very growth or development of the product as an object of consumption. This is the case of a social relation, a situation of prestige, a cultural organization, a process of apprenticeship, etc.

These and other distinct modes of utilization of products often occur in combination, in the sense that the goods and services provide their utility (or multiple utilities) to the degree that they are there, that they act, that one acts with and through them, and that they grow and their potential unfolds. The important thing is to understand that there are as many modes of utilization of goods and services as there are types of goods and services and modes of satisfying people’s needs and desires.

Seen now from the standpoint of its subjective element, the act of consumption is the satisfaction of one or various needs or desires by active subjects. The satisfaction of the subject’s needs can also involve a simple act or a complex process, with different intensities and meanings.

Of course, the transformation of the subject does not necessarily have to be understood as a physical transformation resulting from a material assimilation of the energies and information contained in the product. This happens in forms of consumption relative to particular types of goods, such as food and other materials. But we have already seen that there are various classes of goods, modes of utilization, and needs to be satisfied. It should be understood, then, that just as objects are transformed in the act of consumption, so too are subjects. Consumption can transform the subject by causing an illness, a change of appearance, or personal growth, or by enabling the deployment of personal abilities, the establishment of new social relations, cultural development, etc.

Considered synthetically, the act of consumption is revealed to be, in essence, a a process of transformation, or more exactly, a double process of related transformations in the goods and services consumed and the subjects who consume them. In a certain sense, consumption can be understood as a process of exchange and interaction between subjects and products through which, on one side units of energy and information that are in economic products are in some way transferred (physically, symbolically, relationally, as values, etc.) to the subjects and on the other hand certain energies and information are transferred from the subjects to the objects of consumption. It is these exchanges of energy and information that produce the transformations experienced by both the subject and the object of consumption. These exchanges of energies and information are what produce the transformations that the subject and object of consumption alike experience, keeping in mind that in these interactions that which comes out of the object is not the same as that which the subject receives, and vice versa.

Now we can examine these concomitant and interrelated transformations beyond the simple form of the act of consumption, at the level of the process in its entirety. This means deepening various concepts that we have already deployed, starting with that of human needs, aspirations, and desires.

66. - The concept of “needs” has been the object of important reflections and interesting studies, giving rise to a very broad conception of what a person needs in order to live and thrive, and yet, by itself, “needs” does not adequately express the combination of motivations and impulses from which economic demands emerge. For that reason, we prefer the expression “needs, aspirations, and desires.”

“Needs” implies “lacks” and has a connotation of urgency and necessity that is not true of all requirements of human consumption. For this reason, although the concept of needs used in Economics is supposed to encompass all the other motivations underlying consumption, we prefer to explicitly formulate the concept in broader terms. This helps us keep in mind the variability, multiplicity, and indeterminacy of the motives and impulses on which the entire economic edifice rests. For the sake of brevity, we do at times refer to “needs,” using the term as shorthand for all the motivations and impulses that may take the form of economic demand (through one or another circuit) and thus promote the production of goods and services oriented to their satisfaction, by any type of economic unit. “Needs” should be understood this way not only with respect to what follows but in every part of our study.

We do not presume to offer a theory of human needs, aspirations and desires, which would require an interdisciplinary study in which psychology would have to play a central role. But, even in the narrow framework of Economics, it is indispensable to have some form of classification that permits us to orient not just our analysis of consumption but also any proposals for actions to be taken improve it. If well being and quality of life depend on the degree and ways in which all human needs are satisfied, it is crucial that we acquire a comprehensive vision of them.

It may be that the question of terminology is related to polemics between those who think that human needs are definite, few, universal and unchanging (even if socially and historically determined) and those who maintain that they are indefinite, innumerable, and subject to constant change. People whose strategy prioritizes centralized technical and political economic planning would seem to adhere to the first position, while the second view seems to correspond to the argument that the question of what should be produced should be decided by the individual expression of preferences in free market exchanges.

Our own approach is based on an open-ended, but not indeterminate, conception of humans and society, according to which, on the one hand, needs, aspirations and desires are innumerable, complex, and mercurial, and on the other, there is a fairly broad set of needs and desires that are universal, permanent, and recurrent. These two realities are interconnected and articulated, giving rise to different “combinations” of needs and motivations, each always distinct from the others, with no two subjects –whether individuals or groups – being the same. Despite their multiplicity, complexity and combination, all these needs can be grouped in a few categories on the basis of which one can specify a rational order that economic subjects, be they individuals, communities, enterprises or the State, can use to guide their decisions.

Different classifications are possible. In Book Oneiii we referred to the common distinction between basic or essential needs and those that are dispensable or non-essential, as well as between needs whose satisfaction is individual and those that are satisfied socially or collectively. Hoping to overcome the restrictions that the science of Economics has established in its field of study we proposed other distinctions: between physiological needs and spiritual needs, and between needs related to self-preservation and those of conviviality and human interaction, thus establishing a scheme of four types or combinations of fundamental human needs.iv

Manfred Max-Neef has proposed another scheme of needs that broadens the field of economic analysis beyond its traditional boundaries. His “needs matrix” is based on a distinction between two complementary criteria: “existential categories,” on the basis of which needs of being, having, doing and interacting are identified, and “axiological categories” from which are derived needs for subsistence, protection, affection, understanding, participation, leisure, creation, identity and freedom. Combining the two criteria in a six by six matrix Max-Neef identifies thirty six specific types of needs.v Various other classifications are possible and have been developed with more or less success.

While appreciating the merits of other approaches, it seems especially useful for the purposes of economic analysis to focus on the four types of need we offer here. Their simplicity is due to two decisive qualities. First, the categorization is complete, in the sense that all human needs, aspirations and desires, individual and collective and social, can be effectively organized and classified in one or another of the types. Second, once classified, we can clearly identify two crucial axes along which human experience moves and that define its fundamental existential, pragmatic, axiological and ethical tensions: on one side the body-spirit axis, which is related to physiological and cultural needs, and, on the other, the individual-community axis which stretches from the need for self-preservation to the need for social involvement and participation in collective life.vi

In effect, we can conceive of all the needs, aspirations, and desires of the human being and our communities and groupings as tensions between the conservation and development of the body and the spirit, and between the individual self and the social self.

The body – more exactly people in their corporeal dimension; we are part of and are integrated into nature and the material world and thus we propose exigencies, needs and desires whose satisfaction is reached through material goods and services that imply an exchange between humans and nature.

The spirit – or the spiritual dimension of people; in this aspect we search for transcendence and, ultimately, union with the totality of being or with God. That poses radical exigencies, needs, and aspirations that are satisfied through creative, cultural, religious, etc. activities which engage the capacities of the intelligence, will, imagination, memory, intuition, aesthetic sense, and other superior faculties of the human being.

The individual self – the individual dimension of people; the self is to be conceived, manifested, cultivated and developed in its uniqueness, which poses exigencies of autonomy and freedom and is the source of particular interests, motivations, anxieties, and passions starting from the most elemental instinct of self-preservation.

The communities to which every person belongs – as an expression of their social dimension; we need to be included, to participate, to project ourselves and find satisfaction of our needs and desires for affection and conviviality through the establishment of subjective links, life in community, and collective action.

All of these human needs and desires transcend the strictly economic and are satisfied by means of a complex mix of activities of different types which do not always involve acts of consumption. Breathing, for example, is a physiological need that only implies the utilization of economically produced products under very special circumstances. Aesthetic contemplation, philosophical meditation, friendly conversation, are all activities in which extra-economic aspects and dimensions of action are at play. Nonetheless, the satisfaction of many of our needs – physiological, spiritual, for self-preservation and conviviality – implies the use and consumption of goods and services that have been produced by utilization of economic factors and the exertion of labor.

Then there are needs and desires with economic dimensions and contents that do not appear to be satisfied in the process of consumption but rather in the processes of production and circulation. For example, the need or desire to work, to share, to collaborate with others, etc. Moreover, individual and communal needs and desires are conditioned by the technological context and by the market, and imply the use of times that have alternative economic values.

Do we have to consider the satisfaction of these needs and the influence of these aspects to be part of the process of consumption? Yes. Doubt on this question arises from an inadequate distinction between production, circulation, and consumption as separate processes. We have seen that it is not necessary to understand them this way, because we find consumption activities in the processes of production and circulation, and vice versa. This is why needs to work and to share with others are satisfied by utilizing something more than certain economic goods and services: productive factors and enterprises themselves are needed and should be considered also as products of economic activities.

From the point of view of the consumption process what matters here are the needs and desires of people and groups insofar as they make themselves felt in the economy as exigencies, demands, motivations, or preferences for specific produced goods and services whose utilization permits, favors, conditions or contributes in some way to their satisfaction.

Understanding consumption in this way permits us to deepen the understanding of its subjective side. “Needs” alludes to a lack made manifest by a subject and that must be satisfied because it appears to be indispensable for human life. We know well that a great part of economic activity is motivated by such truly imperious necessities; but, in fact, the greater part of production is probably oriented to giving fulfillment to desires and aspirations that are strong, intense, but do not at all compromise the continuity of individual or social existence.

The distinction between what is a need and what is a simple desire or aspiration turns out to be hard to draw, in any case. For example, we have the need to feed ourselves, which could mean ingesting a certain quantity of proteins, calories, vitamins, etc. But feeding ourselves beyond a certain minimum, with specific foods that are most appetizing to us, can not be said to be a question of need but only of desire. On the other hand, living in community with other people, living in freedom, can be as necessary for subsistence as other “basic” needs, its absence can also lead to death.

It is more than a question of specifying the distinction between the indispensable and the optional. To understand consumption we have to recognize that its source is found in all objective or subjective situations which drive subjects to obtain and utilize economic goods and services. The origin of consumption is not simply a passive “lack” but the positive action of human and social forces, lacks, too, being positive in this sense as they become active forces that require satisfaction.

It is fundamental to understand consumption in this way in order to understand the process of transformation of the subject that it signifies. The idea of “lack” reduces the understanding of consumption to an activity that fills a vacuum, at least for a time, until through use and destruction of the product the vacuum or lack returns and makes itself felt. Consumption appears to be a permanently reiterative and recurring process in the face of needs that reappear periodically in the same form. Although some acts of consumption that can be explained this way (for example, at least partly, eating), the generalization of this idea implies a mechanistic reduction of a process that presents many other forms, characteristics and qualities.

People and communities are not motivated only by what they lack but also by their potential and the capacities they wish to cultivate and use, in order to be more and to be able to do new and greater things that express that which they are and allow them to project themselves beyond that which they have managed to be up to this point. The actualization of potential and the development of capacities are energies that motivate the permanent search for the means of achieving them, becoming a force oriented to the consumption of ever new goods and services. Thus one can understand consumption as a dynamic process, which does not appear solely as reiteration but as growth and change, giving place to processes of expansion and development.

It also means that the transformations experienced by the subjects of consumption are of various types and present different dimensions and qualities. The result of any act of consumption is always some kind of change, as tiny as it may be, in the subject that carries it out.

This being the case, each act of consumption takes place in conditions that are to some degree different from those that prevailed in the previous act of consumption. If I have eaten one type of food I will likely be looking to eat something different the next time, or I will be more or less demanding with respect to the quantity and quality of the food. By visiting an art museum I cultivate my capacity for aesthetic appreciation and will be differently disposed in the future to use particular works of art in the satisfaction of my cultural needs. If my experiences of conviviality and bonds with others have taken a particular form, I will probably be looking for something different in the consumption of goods and services related to social relations than if I had never had that experience. And so on, in every case, which explains the production of ever new and varied goods and services.

Already, at a microeconomic level, consumption by a subject – whether individual or social – should, then, be understood to be a process which can be qualified in different ways. It can be a process of growth, but also of progressive deterioration, or, again, one of continuity and relative stability. And the subject’s consumption can be oriented toward different directions, giving place to the extraordinary variety observed in individual and community preferences and patterns of consumption.

Now, if the needs that give rise to consumption are forces of various types that people and groups voluntarily deploy, consumption can be considered to be ethical and axiologically so. In other words, the values, norms and principles that determine human comportment are at play in the acts and processes of consumption: good or bad, just or unjust, constructive or destructive, etc. Not all economic “needs” are positive, nor is their satisfaction always a good idea. Although the economic may not be the ultimate criterion of discernment with respect to these qualities of consumption, we can find an element of judgment in the analysis of the transformation experienced by the subjects who carry them out. The consumption of goods and services, at the level of the individual, group, or society as a whole, does not always generate well being and growth. It can also imply deterioration, disequilibria, maladjustments, or other negative effects that increase lacks rather than satisfy them.

Among such transformations one should also consider the effects of our use of goods and services on other people, groups, communities, and societies. In reality, each act of consumption affects to some extent – infinitesimal though it may be – all of the members of the society, who share an existential bond. Hegel’s affirmation, which we quote in the epigraph for this book shows its validity too with respect the consumption process. Economists have stressed enough the connections between the different elements of the process of circulation, and also the interconnections in the process of production; recognition of these interrelations and interactions should be extended analogously to processes of consumption.

Understanding needs, aspirations and desires as forces enables us to see that needs make themselves manifest with different intensities and urgencies and that they often “collide.” The collisions occur, not just between people or groups, but even within a given subject, whether individual or collective. The interconnections of needs thus reveal new dimensions that require explanation.

To begin with we see the hierarchization of people’s needs and desires, which has indubitable implications for consumption, and in that way for production and circulation as well. But not all subjects present the same hierarchy of needs: different ideological structures, personality traits, cultural backgrounds, ideological or axiological loyalties, etc. lead subjects to prioritize their needs, aspirations, and desires in very different ways, looking to satisfy each need with different intensity and considering their desires to be fulfilled on different levels and with different quantities, types, and qualities of goods or services.

One aspect that deserves to be highlighted is the fact that needs do not show up all at once, nor can they all be satisfied simultaneously. They are distributed in time and throughout the life of the subjects that experience them. The needs and desires we have in the morning differ from those we have at night, as do those of children, youths, and the elderly. The same holds for communities, enterprises, institutions and states, in their respective dimensions and historical moments. This implies that it is necessary to organize consumption temporally, taking into account the difference between the tempos of production and consumption; a process of rationalization is required.

Moreover, needs do not appear independently or in isolation but always in articulation with others in what may be considered a structure of needs, different for each individual, social class, enterprise, group or community, culture and civilization. Some are complementary, the satisfaction of one need can compensate for the non-satisfaction of another, or the over-satisfaction of one need can inhibit the appearance of a new need. Due to all of this, the immense diversity of needs is not just a matter of degree but also of the quality of their satisfaction.

The hierarchization of needs, their distribution in time and their integration in complex and diversified structures implies that each need, even those that are universal and those that occupy a high rung in the hierarchy, can be satisfied in very different ways, through goods and services that present themselves to subjects as alternatives or options from which to choose, and through an equally varied range of combinations of goods and services as well.

This is valid as much in quantitative terms as in qualitative. In effect, given the different intensities with which each subject experiences needs and desires, the provision of goods and services capable of satisfying them can oscillate widely. One person or community can need more food than another, desire more books and information, require a more intense social life, etc. Inversely, with the same provision of goods and services, people and communities will reach different levels of satisfaction. Needs, too, can be more or less satisfied depending on the greater or weaker correspondence and adaptation achieved between goods and services used and the needs themselves. Needs are always greater and more flexible than the types of goods and services that can satisfy them, and products can reach levels of quality that are notably differentiated. For example, the need to be appreciated by others and to feel integrated into the community can be satisfied by wearing fashionable clothes, participating in a social club, being in solidarity with and providing aid to people in greater need, etc.

In this way the process of consumption – even more than the processes of production and circulation – shows itself to be an field of alternatives and free options, within ranges delimited by the availability of goods and services and by the conditions in which the people’s needs, desires, and aspirations, arise.

People, communities, and societies can establish, in turn, different mechanisms and systems of determination of objectives and means, which will show up in different modes of organization of consumption: by individuals, the State, communities, intermediate bodies, technical organisms, etc. This also is a field of alternatives and options on the social and individual level, which raises questions about possible rationalities of consumption and the ways in which the process can be optimized. But first we must examine the other aspect of consumption, that is, the utilization of products.

67. – Economists have been preoccupied with the concept of goods and services and the difference between them. Take, for example, the formulation of R.G. Lipsey (although we could as easily cite another text with the same result): “The things that are produced by the factors of production are called commodities. Commodities may be divided into goods and services: goods are tangible, like cars or shoes, and services are intangible, like haircuts or education.”vii The author appears to realize the inherent weakness of this distinction between tangible and intangible, which, if we consider his examples, is astonishingly imprecise. Thus, he adds the following, attempting to dodge the question: “This distinction, however, should not be exaggerated: any good is valued because of the services it yields to its owner. In the case of an automobile, for example, the services consist of such things as transportation, and, possibly, status.”

For our part, the distinction between goods and services is not crucial, the joint expression serves to remind us of the breadth of economic production which can not be reduced to material objects but also to a range of actions that satisfy human needs. In this sense, we speak of goods to refer to tangible and intangible economic products, and services to refer to economically produced actions, which, too, can be tangible or intangible. The classification of products must be based on more complex criteria, to which we now turn.

Understanding the urgency of acquiring a broader perspective of economic activity and of the needs that are to be satisfied through its intermediation, Max-Neef adopted the notion of “satisfiers… individual or collective forms of being, having, doing and interacting, in order to actualize needs.” Economic goods, then, are “objects and artifacts which affect the efficiency of a satisfier, thus altering the threshold of actualization of a need, either in a positive or negative sense.”viii

It is the satisfiers which define the prevailing mode that a culture or a society ascribes to needs. Satisfiers are not the available economic goods. They are related, instead, to everything which, by virtue of representing forms of Being, Having, Doing, and Interacting, contributes to the actualization of human needs. (See chapter 4, page 31.) Satisfiers may include, among other things, forms of organization, political structures, social practices, subjective conditions, values and norms, spaces, contexts, modes, types of behaviour and attitudes, all of which are in a permanent state of tension between consolidation and change…

While a satisfier is in an ultimate sense the way in which a need is expressed, goods are in a strict sense the means by which individuals will empower the satisfiers to meet their needs...

To assume a direct relation between needs and economic goods has allowed us to develop a discipline of Economics that presumes itself to be objective. This could be seen as a mechanistic discipline in which the central tenet implies that needs manifest themselves through demand which, in turn, is determined by individual preferences for the goods produced. To include satisfiers within the framework of economic analysis involves vindicating the world of the 'subjective', over and above mere preferences for objects and artifacts.ix

No doubt, Max-Neef shares our intention to “rescue and uphold the subjective element” in Economics, overcoming the mechanistic vision of the discipline, and broadening its horizons in many directions. Nonetheless, the introduction of the concept of “satisfier” as a decisive element of this project seems to us inadequate. On the one hand, the concept is imprecise, ambiguous, and difficult to operationalize. On the other, in his eagerness to underscore the centrality of the concept and distinguish it as much from economic needs as economic goods, he reduces the latter to concrete “objects and artifacts,” and supposes a concept of needs that is extremely abstract and generic, which permits him to assume that they are “finite, few, and classifiable... the same in all cultures and in all historical periods.”x

Thus, for example, one need would be “subsistence” and its satisfiers would be physical and mental health, food, shelter, labor, procreation, rest, work, social and living environment, etc. Goods would be those objects and artifacts that affect the efficiency of those satisfiers, such as bread, a jacket, a bed, etc. But “subsistence” is nothing but a generic notion which covers a range of needs (for food, shelter, work, procreation, rest, etc.) and the same can be said of the needs for understanding, identity, creativity, etc. and their respective “satisfiers.” We thus find that in various cases, the so-called satisfiers are in reality more specific needs and desires, while in other cases they actually identify goods and services.

In other words, the concept of need in Max-Neef is on the same level of abstraction as the one on which we defined physiological and spiritual needs and needs for self-preservation and conviviality. That is, they are synthetic categories used to group, order, and classify numerous needs. On the other hand, the reduction of economic needs to objects and artifacts (leaving aside the notion of “services”) contains the germ of possible new reductivist visions of production and the market.

All in all, Max-Neef’s effort has the value of seeking a new theoretical paradigm that, insofar as it deals with consumption, facilitates the comprehension of substantial and revelatory facts: first, that needs are not independent and isolated from each other but articulated, complementary, integrated and compensatory, forming “structures of needs” peculiar to each individual or social subject. Second, that economically produced goods and services are not only those that are exchanged at specific prices but include cultural, spiritual, and social goods and services, often immaterial, which are also articulated, integrated, and combined in sets and structures of goods that permit the combined satisfaction of needs that are also complex.

Beyond the distinction between goods and services, we understand a product – an objective element of consumption – to be any type of energy and information, combined or individual, simple or composed, that having been economically processed has the quality of being useful for the satisfaction of people’s needs, aspirations and desires or the development of their capacities and the actualization of their forces and potential powers. Consequently, the concept of economic products covers more than the many types of goods and services that circulate in the market, including social organizations, activities, complex situations, a mood, a cultural reality, etc., created through specific economic activities.

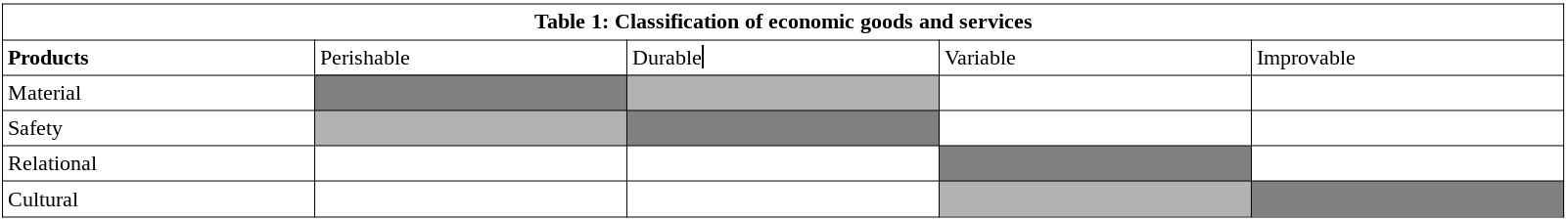

Defined in this way, products can be classified in different ways, some more useful than others for the analysis and orientation of the consumption process. Using two closely related criteria we can formulate theoretically useful classifications: according to the type of needs they satisfy and according to the way in which they are transformed in consumption.

According to the type of need they satisfy we distinguish between products on the basis of the classification of needs we laid out above:

a) Material goods and services oriented to the satisfaction of physiological needs; in this group we find food, clothing, medical care, sports equipment, cooking utensils, domestic items, etc.

b) Goods and services related to safety, meeting needs for self-preservation; including housing, systems of security and protection, police services, defensive tools, weapons, public services protecting people and property, organizations, and political institutions, etc.

c) Goods and services related to social interaction, meeting needs for conviviality and relations with others, such as clubs, circles of friends, festivals and parties, sporting events, centers and services for play and conviviality, postal services and other means of communication, community organizations and much more.

d) Cultural goods and services that serve to satisfy spiritual needs. Included in this group are goods and services related to learning, training, and education (formación), works of art, scientific and cultural knowledge, information, statistics and programs, temples, flags and other symbols, literary works, etc.

All goods and services produced by people in economic units and distributed through some kind of economic relations in the market, whether material or immaterial, fall under this classification. Naturally, and as we shall see later on, certain products have the quality of serving more than one need simultaneously, or they combine and integrate other products in such a way that multiple needs are satisfied together. A perfect example of this is housing, which serves to satisfy the four types of need we identified above. In housing we also see a variety of goods and services at play. Another example is that of a social organization or institution which is an economic product insofar as its establishment and operations require multiple types of work and the use of distinct factors by various economic units. Organizations, too, comprise a wide range of integrated goods and services that serve to satisfy many needs.

On the other hand, the nexus between the type of good and the type of needs it satisfies is affected by the “systemic” character of the needs and goods themselves. For example, a temple is a material good that satisfies needs of the body, for shelter, a place to sit down, etc. but is also used when people there pray to God. A series of architectural and cultural features in the temple directly favor the satisfaction of spiritual and relational needs and aspirations, such that in its material conformation the temple should be considered to be a good that is at once protective, interactive, and spiritual. To take another example, culinary art is a cultural good that is basically made up of knowledge and skills, but is inseparably linked to the satisfaction of bodily needs and desires. We can conclude, then, that this first classification of products presents constant complexities. Let us now consider the other criterion of classification.

According to the ways in which they are transformed through consumption we can distinguish between the following types of products:

a) Perishable goods and services, consumed at one go and then gone or no longer useful for the purpose for which they were created. Many products aimed at satisfying physiological needs are of this type.

b) Durable goods and services that can be used over time or repeatedly at distinct moments, losing their utility or wearing out very slowly over a long period of time. Many goods and services that satisfy needs of self-preservation are of this type.

c) Variable goods and services, that is, those that exist to the extent that the activities that create them continue to be used, resulting in variations over time, growing and gaining power or fading depending on the circumstances. Many of the goods and services that meet needs for harmonious social existence are of this type.

d) Improvable goods and services, those which are improved through use, becoming better suited to continue satisfying needs: in this category we find all those products that are consumed through – or whose acts of consumption imply – the realization of creative activities and the development of the subject’s skills. Many goods and services destined to satisfy spiritual needs present these characteristics.

Beyond its use for classification, the criterion of transformation reminds us that the change that the objective element in consumption undergoes can be instantaneous, rapid, slow, or progressive and take the form of deterioration and loss of its original energy and information just as much as its growth, maturation or integration into a higher reality.

Combining both criteria of classification we can set up a matrix which specifies 16 types of products. Particular cells are shaded to indicate the degrees of frequency of the respective combinations, underscoring the correspondences that tend to arise between the types of needs that these products satisfy and the modes in which they are transformed when consumed.

Now, the transformation that the different products undergo in their consumption does not only depend on their intrinsic characteristics or qualities as goods or services but also and much more decisively on the way in which the act of consumption is carried out. In effect, we have already seen that in the act of consumption the subject is the active element, the one who realizes the action, while the product is the passive element, receiving the action. Thus it is that, depending on the mode of action of the subject, consumption of a given product can be effectuated in such a way that it is promptly destroyed or that it lasts over time, that it deteriorates and loses value or is improved and gains value. We think, for example, of the different ways that a bicycle can be used, or a house, an institution, a work of art. We could discover, in each of these cases, modes of consumption that destroy, preserve, value, use creatively, etc. the goods in question.

When assessing the quality of consumption one should, then, take into account not only the transformations undergone by the subjects but also those we see in the goods and services consumed. Especially because the quantity and quality of satisfaction of needs and desires that they can offer depends on the mode in which they are transformed. A better maintained bicycle can offer greater satisfaction of the need for transportation and recreation, while careless use of the same bicycle can satisfy a need for aggression or a desire to harm the owner of the bicycle.

To take another example, while the attentive and careful reading of a book can undoubtedly provide a much higher satisfaction of the need to know, a hasty or careless reading may be enough to satisfy the need to show one’s colleagues that you read the book and are in a position to critique it.

How many goods are needed to satisfy a given need or desire, too, depends on the way in which the act of consumption is carried out. The more thoroughly we extract and utilize the energy and information present in a good or service, the less of it we probably need to satisfy the need in question.

The various modes of utilization of products also shape the various rationalities of consumption. Before entering fully into the question we need to examine one aspect of the relations that arise between the concomitant processes of transformation of the subjective and objective elements of consumption.

68. The point that we want to focus on here refers specifically to the links that exist between the economic needs of subjects and the goods and services destined to satisfy them.

Conventional Economics takes up this theme in the framework of so-called “theories of consumer behavior in the household economy” or “the theory of consumer choice, preference, and utility.” These theories focus on the choices that consumers make between different available goods as a function of maximization of the utility to be obtained, taking into account the restrictions given by rent received or by relative prices. The principle theoretical elaborations here are: marginal utility theory, revealed preference theory, and indifference curve analysis.

The main conclusions of these theories with respect to the relations between consumer utility (satisfaction of needs) and the goods and services offered on the market are as follows:

a) To the extent that the quantity of a good increases, its marginal utility for the consumer (the utility of the last unit consumed) declines. Some goods can even have a negative marginal utility: instead of increasing satisfaction, the consumption of new units produces disutilities. For each good there exists a “utility curve” that expresses the utility obtained by the consumer for different quantities of the good.

b) If goods were free and abundant, people would consumer them up to the point when their marginal utility equaled zero. But as they have a cost, it is necessary to distribute that cost between various useful goods and services, in such a way as to reach the maximum possible utility with the available resources. Theoretically this is achieved at the point when the marginal utility of the last cent spent on each good is the same.

c) When spending, consumers choose between different goods. For each good there exists a marginal rate of substitution, which expresses how many units the consumer is disposed to sacrifice in order to gain the utility of another good. When we consider the substitutability of two goods, we run into the fact that at different proportions, their consumption is considered of equal utility; these correspondences give rise to an indifference map. By revealing their preferences, consumers show that their choice between the various combinations of equal utility will be determined as much by the allocations in their rent as by variations in relative prices.

d) In making choices, the consumer is conditioned by the characteristics of the goods as well as by their own needs. This is seen in the fact that certain goods are more substitutable than others, which is reflected in their distinct marginal rates of subsitutability. There are goods that are perfectly substitutable and goods that are seen to be perfectly complementary (no substitutability is possible between them). This gives rise to the notion of elasticity, which indicates how sensitive quantities of a good consumed are when its relative price is modified.

This is as far into substance as economic theory goes; the latest developments in the theme do no more than add complexity to the problem, incorporating details and particular cases that do not change the analytical framework, progressively incorporating new variables, like the stock of wealth, consumer preferences over time, and uncertainty.

But the theory continues to be based on what is a fairly simple relation between economic goods and the utility they provide in the satisfaction of needs. There is a correspondence between goods and needs, which is not so strict as to rule our the satisfaction of the needs by different goods. There is a relation between quantity of goods and the satisfaction of needs, which is not directly proportional but adopts the form of a utility curve, accepting even disutilities. In combining goods, the consumer seeks to optimize the combined effect of all their various acts (expenses) of consumption. (In reality, conventional Economics is not interested in needs as such but in the utility that goods and services provide consumers; “utility” is treated as a generic notion that synthesizes all the satisfaction the subjects make of their needs, independently of what they are.)

This is all, and it’s not much. We do not view it with disdain and we need to incorporate it in the comprehension of the consumption process. But it is essential to recognize that the relation between goods and the satisfaction of needs is very much more complex.

One of Max-Neef’s main contributions – in the aforementioned text that collects the joint work of a group of Latin-American researchers – consists of posing the problem in its real complexity. “It is not only a question of having to relate needs to goods and services,” they write, “but also, to relate them to social practices, forms of organization, political models and values. All of these have an impact on the ways in which needs are expressed.”xi More precisely, Max-Neef’s idea is that fundamental human needs conform to a system in which we find complex relations of simultaneity, complementarity, and mutual compensation between various needs. The key is to replace the assumption of linearity (according to which consumption depends on the preferences of consumers for determined goods) and work with the systemic assumption.

On the basis of this assumption the different “satisfiers” are later analyzed in order of the effects they produce on the system of needs, leading to the definition of five principle types:

a) Violators or destroyers which, “when applied with the intention of satisfying a given need, not only... annihilate the possibility of its satisfaction over time, but also… impair the adequate satisfaction of other needs.” (Max-Neef et al. 1992. pp 32-36)

b) Pseudo-satisfiers, “elements which generate a false sense of satisfaction of a given need. Though not endowed with the aggressiveness of violators or destroyers they may on occasion annul, in the not too long term, the possibility of satisfying the need they were originally aimed at fulfilling.”

c) Inhibiting satisfiers, those which “generally over-satisfy a given need, therefore, seriously curtailing the possibility of satisfying other needs.”

d) Singular satisfiers, “those which satisfy one particular need. As regards the satisfaction of other needs, they are neutral.”

e) Synergic satisfiers, “those which satisfy a given need while simultaneously stimulating and contributing to the fulfillment of other needs.”

Beyond the strong value connotations that in one way or another bias the comprehension of this classification, the author’s contribution is essential insofar as it reveals the true complexity of the existing connections between the satisfaction of needs and the utilization of products. In the interest of properly understanding this complexity, we have already criticized the insertion of a vague and general layer of “satisfiers” between needs and goods. Let us say, individual and social subjects seek to satisfy their complex and interrelated needs by utilizing complex interrelated groups of goods, configuring in this way a consumption process made up of interacting consumption acts or activities.

In the interaction between both sides of the consumption process the influences of needs have on goods and services stand out first of all. If needs are not just passive lacks but operant forces that seek satisfaction, it is obvious that they will determine in great measure the types of goods and services that economic subjects demand of enterprises, thus incentivizing their production.

This influence of demand on supply, nonetheless, should not be understood in a simplistic manner, as certain conventional Economics does when it emphasizes “consumer sovereignty” – the notion that by demanding and buying a given good or service consumers are “voting” in favor of the production of that product. This idea is not entirely meaningless, but it is necessary to understand that needs are interrelated, “systemically” interacting. As a result, the orientations and exigencies they convey to the producers correspond not to individual “votes” but to the structures of complex needs and the modes of satisfaction that we analyzed above. Those structures and modes depend on the social, cultural, ethical and political conformation of people, communities, enterprises, and society as a whole. So, a combination of extra-economic aspects which configure the mode of being of economic subjects and the society in which they develop shape consumption (and thus condition production). An individualist culture, a communitarian culture, or a mass culture give rise to very different forces that, from the side of the subjective element of consumption, also shape its objective element in various ways.

Understanding needs as forces and not as simple lacks permits us to visualize the real potential of consumers in the structuring of markets and production, a role which remains fairly obscure if needs are seen as simple lacks to be filled in by respective goods and services.

But as needs can be satisfied in different manners and by utilizing a variety of goods and services, it should also be recognized that the forces of supply (enterprises) have significant autonomy in determining the goods and services they produce, which, through the market, come to be used by consumers. The fact that certain goods and services “create” needs and desires that they satisfy is well known. It can also be observed that the provision of certain goods not only awakens the need and desire for them, but can inhibit and relegate to a second level other needs, globally altering the structures of needs that subjects – people, communities or societies in general – manifest.

Now, from the moment a good can satisfy different needs and have different effects on different subjects, and as needs in turn can be satisfied by various goods, each subject’s structure and hierarchy of needs has effects on those of others. The choices made by each consumer influence not just production but also the forms in which other subjects satisfy their needs and how they consume.

Let’s take a concrete example. The need for entertainment and recreation can be satisfied with a television or by playing games or community activities. When a person, or many people, choose television, they are influencing others who might have preferred to join in community activities but now watch television. The same thing happens in reverse: if people begin to choose community activities it is probable that others whose needs can be met perfectly well by watching television will seek to satisfy them through community activities. Moreover, since television is a good that satisfies various needs, such as the need for information, its penetration into the need for recreation leads many people to begin to prefer to get their information from television as opposed to radio or print media. On the other hand, community activities also serve to satisfy needs for information, such that the choice of community activities for recreation brings with it an incentive to get information through oral or written communication and generally in other ways than television. Thus in the interaction between goods and needs we see the “systemic” character of both sides of consumption.

There is also a dialectic in consumption processes – a complex relation of forces. On the one hand there is the struggle and interaction between producers and consumers in which, according to the particular characteristics of the market and the capitalist economy, one side comes to dominate the other. We will see later on that when the market is more concentrated with a higher degree of centralization and even monopoly of production, the producers are much stronger than the consumers who they hold down. Consumption becomes less efficient and, as a result, fewer of the needs and desires of the people are satisfied.

On the other hand, interaction among consumers leads to reciprocal influence and the existence of consumers with more powerful demands can give rise to clusters of influence that have a decisive impact on the general structures of consumption. It is easy to understand how concentration can give rise to processes of homogenization and standardization that impoverish the satisfaction of human needs and desires, causing a deterioration in the general process of consumption.

Taking into account these complex relations between subjective and objective elements in the process of consumption enables us to understand the question that we posed earlier, when analyzing the circulation process. How is it that sometimes goods and services are not good? How is it that one can say that the economy also produces and circulates “evils and prejudices”? Rather than qualifying the economic products themselves in this way, our analysis leads us to identify the positive or negative connotations of good and services based on the effects they have on human needs and the ways they are satisfied. As products they can influence the structure of needs, altering their hierarchy and priorities. At the same time, the effects of goods and services spread out in various directions, affecting not just the person or group that directly consumes them but other connected subjects as well.

We can schematize this set of relations, moving toward a new and more complete classification of goods and services (complementary to the two that we proposed based on the criteria of the type of needs satisfied and way in which they are transformed in consumption). In sum, the criterion of classification of goods and services that we will now use is the way in which needs are satisfied and shaped.

According to the type of subjects whose needs are being satisfied we can distinguish between goods and services for individual consumption, group or communal consumption, and public consumption.

According to the number of needs that they satisfy we can distinguish between, simple goods and services (those that satisfy one need or desire) and those that are complex (those that satisfy simultaneously a number of different needs or desires).

According to the effects that their consumption has on other needs, we can distinguish between neutral goods and services (that do not affect other needs and desires), inhibiting goods and services (which reduce, harm, or negatively affect other needs in some way), and expansive good and services (which broaden, encourage or positively affect other needs in some way).

Naturally, these neutral, inhibiting, and expansive effects can refer as much to the needs of individual, communal, or public subjects themselves who use the products (primary consumers), as to third parties affected by the primary consumption, who in turn can be individual, communal, or public. We can call the latter group secondary consumers since if they are not the ones who directly perform the basic act through which products are used, they nonetheless end up transformed by these products, through indirect consumption.

Combining these different aspects we discover the existence of an immense spectrum of goods and services, ranging from products consumed by an individual satisfying a simple need with no effect on their other needs, but with negative collateral effects on the needs of a secondary individual, to products of public consumption that simultaneously satisfy various needs of primary consumers, inhibiting some needs of individual and group secondary consumers, but strengthening the needs of other public consumers.

These criteria of combined classification are not just useful for making an exhaustive classification of all goods and products. They are also useful for better identifying the effects different types of products have on other subjects and the influence their needs have on different types of products. We can see, for example, that cigarettes are a product for primary consumption by an individual subject or secondary group that is affected by second-hand smoke, and that it has inhibiting effects on both the primary and secondary consumers. To take another example, a training course is a service consumed by a primary group that simultaneously satisfies various needs, both individual and group, and has other secondary consumers, individual and public, who expand their needs as a result of the same course.

From a theoretical point of view, these classifications and distinctions are important for understanding the different rationalities of consumption. In effect, the joint consideration of these characteristics and qualities of goods and services, of their different classes and their different modes of utilization, with the characteristics, qualities, classes and modes of satisfaction of needs, aspirations and desires of the people permit us to pose with a certain rigor the question of the rationalities of consumption and of the forms in which it might be optimized, a fundamental economic question that the discipline has barely taken into consideration.

- iEconomía Solidaria y Mercado Democrático (1984, Programa de Economía del Trabajo, Academia de Humanismo Cristiano, Santiago); Las Donaciones y la Economía de Solidaridad (2018, Ediciones Universitas Nueva Civilización, Santiago); Crítica de la Economía, Mercado Democrático y Crecimiento (1994, PET, Santiago); Empresas de Trabajadores y Economía de Mercado (1991, PET, Santiago); Desarrollo, Transformación y Perfectionamiento de la Economía en el Tiempo (2000, Universidad Bolivariana, Santiago,); Lecciones de Economía Solidaria (2009, Uvirtual.net, Santiago); Tópicos de Economía Comprehensiva (2017, Ediciones Universitas Nueva Civilización, Santiago)

- iiVilfredo Pareto’s idea that a solution is optimal if it has positive impacts on some actors without negative impacts on others.

- iiiLas Donaciones y la Economía de Solidaridad, 2018, Universitas Nueva Civilización, Santiago de Chile. - MN

- ivLas Donaciones, p 150. Conviviality is used here in the sense of equitable and reciprocal cultural, economic, social and political relations, as in Ivan Illich’s Tools for Conviviality. 1973. Harper and Row. - MN

- vMax-Neef, M. 1992 ‘Development and human needs,’ in P. Ekins & M. Max-Neef (eds.) Real-life economics: Understanding wealth creation (1992): 197-213. (Accessed online: https://timorissanen.files.wordpress.com/2019/06/max-neef_1992_fundamental-human-needs.pdf) - MN

- viThe body-spirit axis can be considered to include our relations with the environment and non-human actors. - MN

- viiLipsey, Richard G. 1975 An Introduction to Positive Economics. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. P 51 (Accessed online: https://archive.org/details/introductiontopo0000lips/page/n5/mode/2up) – MN

- viiiMax-Neef et al., 1992. p32

- ixMax-Neef et al., op cit. pp 26-28

- xMax-Neef et al., op cit. p20

- xiMax-Neef et al., op cit. p27

Citations

Luis Razeto Migliaro, Matt Noyes (2023). The Process of Consumption and the Means of Achieving Well Being: Excerpt from Comprehensive Economic Theory. Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO). https://geo.coop/articles/process-consumption-and-means-achieving-well-being

Add new comment